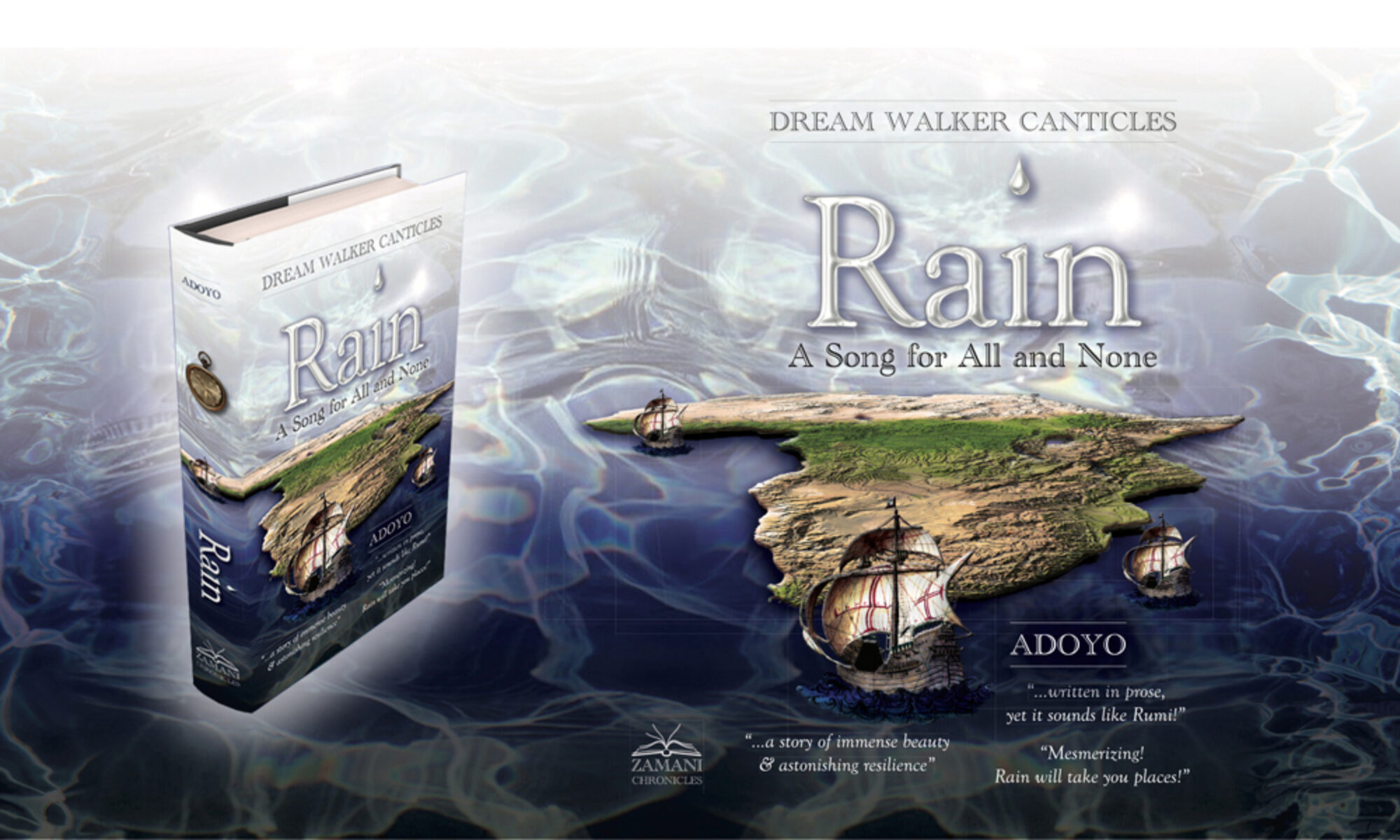

Dear Reader, when I first set pen to paper to write the story of Rain, I took it for granted that the completed text would take the form of a novel. However, I never nurtured aspirations of becoming a novelist, or a writer of any kind really; the uncomplicated joy of reading to my heart’s content was always enough for me, and the treasure trove of written matter around me gloriously abundant. I started composing Rain for the simple reason that I wanted to commit to written record the voices of storytellers of yore who could breathe song into lives and worlds with seamless ease. I wrote as one transcribing the words of a song once upon a time beloved, but now fading in waning memory. The song I heard and tried to write down was itself a meditation on History examined through the lens of Oral Tradition. I found, in listening to this meditation, repeated invitations to unwind from quotidian tensions, to attend more closely to the beauty of the moment with deeper reverence. The turns my pen took as if by intuition traced a journey through living memory unbound from the shackles of time, and I finally understood that the book I was writing was just the kind of song I had heard growing up.

Like many songs, the voice that sings and holds the principal melody in Rain is joined by other voices, sometimes in harmony and consonance, sometimes in contrapuntal play, and sometimes in jarring dissonance. This principal voice, I realized quickly, was that of my own great-grandmother, Rebecca Apiyo Nyonditi Nyariba Atiga ng’ute bor Nyodongo, the matriarch whom we all simply called “Ruba.” Ruba’s name, all by itself, already told the story of her own journey through life from birth, to marriage and motherhood, to maturity: she bore the name of the first of twins (Apiyo), the daughter of Onditi (Nyonditi), born of the River (Nyariba), a graceful pearl (Atiga ng’ute bor), and descendant of Odongo (Nyodongo). Even her Christian name, Rebecca, bore witness to the matriarch she eventually became. Throughout my childhood, Ruba breathed life into the memory of generations through song. She sang histories and poetry, allegories, and parables, and her songs recounted stories of creation, of heroes, of retribution, of justice. Her voice closely guided my quill and continues to resound in my ear still.

I cannot say whether any single notion or event can account for the growing prominence of Ruba’s voice in my imagination as I grew up and grew older. But I remember, for example, how when I applied for graduate school, it was her voice that echoed through the Statement of Purpose I submitted. The admission committee later told me that it was that voice that inspired them to invite me to the program of my choice. Rain is a testament to the continued guiding strength of that voice.

And each of the multitude voices and stories flowing into Rain is a vital tributary to a dynamic polyphony that explores and illuminates the conflict between sanitized histories of colonialist aggression and the unvarnished accounts of their savagery. It will not surprise readers familiar with the voice of Dante Alighieri’s Commedia that the Great Poet’s most important animating influence in Rain is the way it emboldens this story to draw back the veil of recorded History and bear witness, with an unflinching and conscientious gaze, to the brutality of the agents of colonial dominion — figures celebrated for the Age of Discovery whose incursions wreaked unconscionable horrors on peoples around the world for Coin in the name of Church and Crown and set the precedent for presumptuous appropriations like the Scramble for Africa centuries later. The poetic voice of Dante artifex also permeates the comprehensive structure of Rain, from its general architecture to the network of internal memory manifest in the story’s narrative refrains, as well as the musical rhythm and flow of the storyteller’s language. The most dulcet tones of Dante’s voice resonate deeply in the contemplative strains of Rain devoted to singing the unspoiled beauty of Nature in the bounty of Africa’s expansive savanna grasslands, gleaming equatorial mountain glaciers, opulent Rift Valley, cascading waters and wending rivers, and shimmering Great Lakes.

Other familiar voices that resonate throughout Rain — thanks to Ruba’s uncomplicated faith, and thanks to the instruction of teachers from earliest childhood — include Bible verses that saturate the popular imagination of the world of the story’s protagonists. Many of these verses are quoted in the text from a number of different translations of the Old and New Testament. The four Bible voices in Rain include:

- The Vulgate Latin Bible translated by St. Jerome.

- A Portuguese translation of the Gospels and Epistles of the New Testament published in Porto in 1497 based on an earlier Spanish translation of the Bible by Gonçalo Garcia de Santa Maria: Guilherme Parisiense, Evangelhos e Epístolas com suas Exposições em Romance, translated to Portuguese by Rodrigo Álvares. Although Martin Luther’s translation of the Bible to the German language enjoys greater renown for making the Scripture more readily accessible in the vernacular, it is all the more fascinating to see in the evidence of these Spanish and Portuguese translations that Luther was not the first, but rather part of a practice that extended over several decades, if not centuries, before his German translations appeared. The significance of this Portuguese voice in Rain resides in the fact that it serves as witness to the availability of Scripture to the literate speakers of the language from at least the middle of the 15th Century when Pope Nicolas V issued the Papal Bulls Dum Diversas and Romanus Pontifex, both of which figure significantly in the polyphony of Rain.

- The third Biblical voice with deep resonance in Rain includes the English translation commissioned by James Charles Stuart, King of Great Britain and Ireland, published in 1611 — less than a century after the first translation of the New Testament into English by William Tyndale appeared in 1526. The influence of the Authorized King James Version extends beyond the liturgy of the Protestant Church and into the linguistic timbre and rhythm of literature for the centuries that followed its publication, integrating seamlessly into English-speakers conception of Scripture and the voice of God.

- The forth Biblical voice in Rain rises from its more recent translation into the Luo language, Muma Maler, published by the Bible Society of Kenya and the Bible Society of Tanzania in 1976. Like other translations in local languages of East Africa and beyond, this translation is a testament to the evangelical vigor and success of the Christian missionaries that served as the velvet glove over the iron fist of the colonial enterprise.

Less nuanced and unabashedly ruthless are the voices of Popes in Rome who mandated brutal aggression against Peoples across the world in the name of God and the Catholic Church for the glory and legitimacy of the Crowns of Portugal and Spain in the 15th Century. Several readers of Rain have noticed the obtrusive violence of these voices in contrast to the story’s natural flow. Their incursion takes the form of the ritualistic refrain of passages from a series of Papal Bulls issued by Pope Nicolas V (1447-1455) and Pope Alexander VI (1492-1502) authorizing and encouraging the Portuguese and the Spanish monarchs to encroach upon and take for themselves the riches of the Peoples in those parts of the world from which the Iberian agents of colonial dominion wanted to wrest profit.

- The Papal Bull Dum Diversas — issued to Dom Afonso, King of Portugal, on 18 June 1452 — emboldened the crown’s already robust maritime ambition to map a trade route to India to further press their efforts with the zeal of Crusaders. In authorizing Afonso V of Portugal to reduce any “Saracens and pagans and any other unbelievers” to perpetual slavery, Pope Nicolas V established the legal and moral authority for the campaign of terror that European slavers and colonialists unleashed, unchecked, upon the Peoples of the world that they subsequently assailed.

- On 8 January 1454, Pope Nicolas V’s Bull, Romanus Pontifex, reaffirmed the Catholic Church’s mandate to lay claim on the homes and resources of the Peoples that the agents of the Portuguese Crown beset, repeating the call to exploit and enslave their persons wherever they lived. With this reiteration of the tenets of the previous Bull Dum Diversas, Romanus Pontifex extended the presumption to dominion over the lands of others to the Catholic nations of Europe during the Age of Discovery.

- Before the century’s end, on 4 May 1493, Pope Alexander VI again affirmed the aforementioned mandates in the Papal Bull Inter Caetera, making sure to state that Christian nations were exempt from being subjected to dominion by other Christian nations.

Awakening to the brutality hidden behind the veil of bowdlerized History also draws attention to the silences of those poets who wielded their craft in service to glorifying agents of colonial aggression and whitewashing the campaigns of terror and obliteration that these putative heroes carried out around the world. Rain owes a debt of gratitude to those chroniclers among Vasco da Gama’s contemporaries and travel companions, like João Figueira, who recorded accounts of da Gama’s three voyages around the coast of Africa to India and back. Among the historians of the early 1500s who wrote and published details about the ships and crew of Vasco da Gama’s voyages, timelines and related documents, the most revealing voices in Rain include those of:

- Gaspar Corrêa’s Lendas da Índia (1550-1566), available in English translation as The Three Voyages of Vasco da Gama, and His Viceroyalty, from the Lendas Da India of G. Correa. Accompanied by Original Documents. Translated by Henry E. J. Stanley. London, 1869.

- Renowned historian João de Barros, author of Décadas de Asia (1552), and sourced through Da Asia de João de Barros e de Diogo de Couto, vol. 2. Regia Officina Typografica, 1777.

- The highly regarded and widely translated historian Fernão Lopez de Castaneda, author of História do descobrimento e conquista da Índia pelos portugueses (1551), which is available in English translation in The First Booke of the Historie of the Discouerie and Conquest of the East Indias, Enterprised by the Portingales, in their Daungerous Nauigations, in the Time Of King Don Iohn, The Second of that Name, translated by Nicholas Lichefield (1582).

- Alvaro Velho and João de Sá, A Journal of the First Voyage of Vasco da Gama, 1497-1499, translated by E. G. Ravenstein.

Together, the voices of these chroniclers and historians — whose works drew upon first-hand accounts and contemporary documents pertinent to Vasco da Gama’s voyages — add an illuminating note to the willful silences of paradoxically panegyric myth-making in the face of empirical accounts. And few examples of this willful myth-making are as roundly celebrated as Os Lusíadas, the epic poem immortalizing Vasco da Gama as the greatest son of Portugal, written by Luís Vaz de Camões.

Despite the acrid taste of History’s reality, the song of Rain is sustained by the resilience of deeply rooted cultural traditions that persist to this day, even if only in the fading echoes of forgotten songs.

And so, I invite you, kind reader, to listen with a benevolent ear and an open heart to the poetic meditation on History that resounds through the voice of Oral Tradition, and to discern the truth born of allegory in Rain – A Song for All and None.