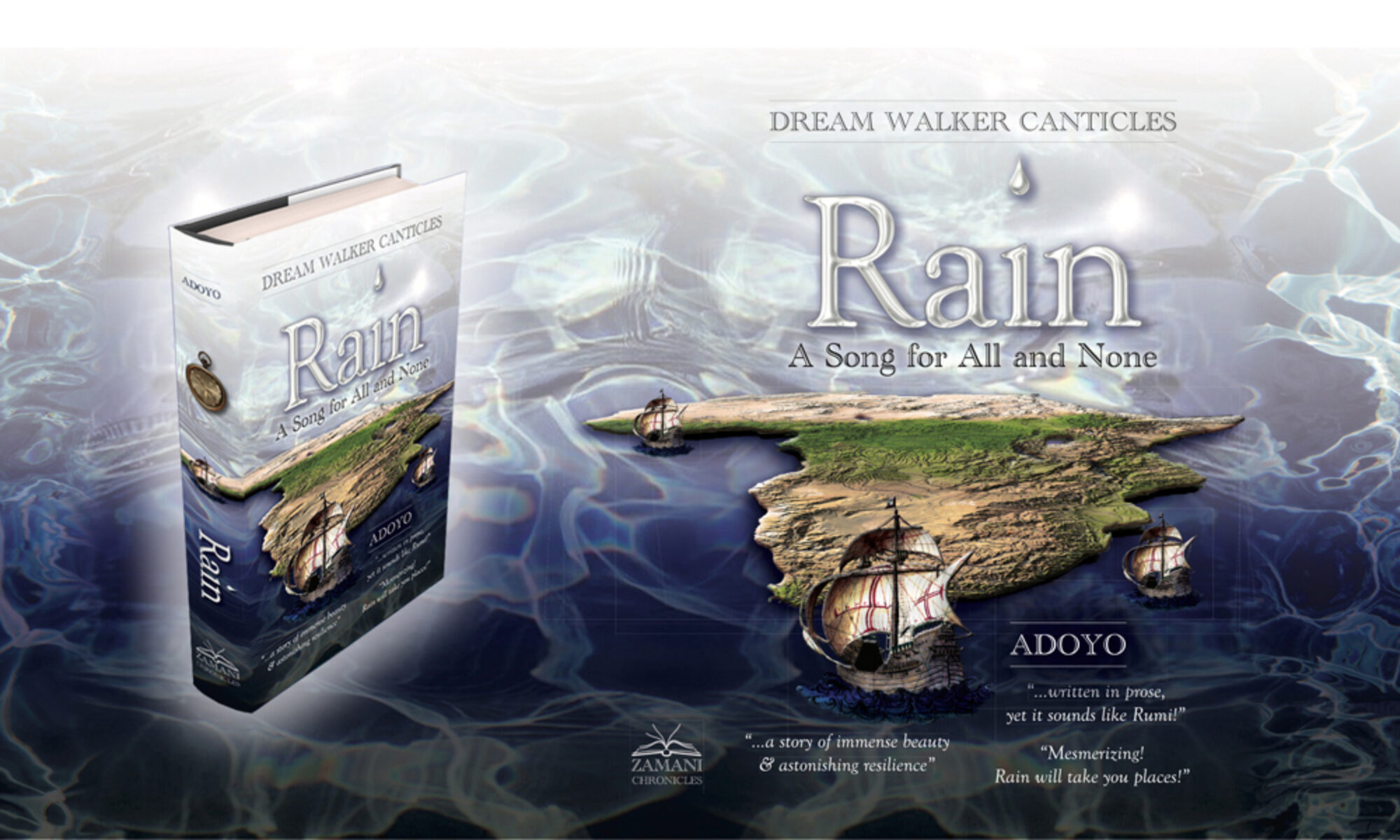

Book VI

Canto Forty

So Rebecca charged Solomon to show Hehra around the city during her stay. Her younger son, Jonathan, was not yet back home from university, so Solomon would have to make do on his own. Rebecca suggested that they visit the British Library and then the British Museum, and then she told them to be sure not to forget St. Paul’s along the way. When the pair returned home on the third day, and Hehra could not stop talking about Westminster Abbey, Rebecca listened captivated while they prepared supper together. Solomon sat nearby, just out of their way, his shining eyes collecting every word Hehra uttered. Things that he had long learned to take for granted seemed to electrify her. She mused with delight that Westminster Abbey was over a thousand years old. Did they know that it was the site of William the Conqueror’s coronation? And that his cousin or grand uncle Confessor was buried there, too? How did it feel to live so close to the place where Newton was entombed? Solomon had played host often, both for work and for friends, and he frequently took his guests to see Big Ben and then Westminster Abbey along the usual visitor’s London tour. Now here for the first time, a guest’s enjoyment was not just satisfying and amusing, it drew him in and made him curious to feel it all as she did. But he did not ask her to explain, he simply listened and watched, enjoying in his turn her hushed exhilaration and the pleasure she drew from revisiting monuments of a thousand-year story that was ever present to her memory’s eye.

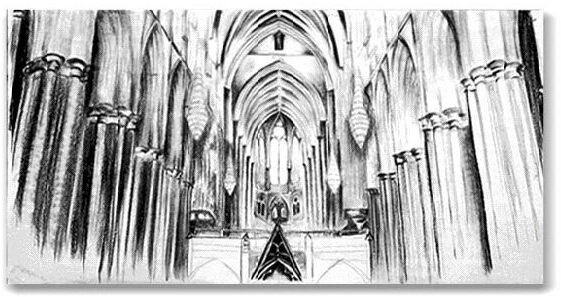

And nothing had compared, in Solomon’s eyes, to Hehra’s elation when the choral evensong began to resound. They were getting ready to leave Westminster Abbey, after nearly three hours among the tombs and memorials in that most mannered stone forest built for God and kings, when the choir’s voice emerged, unadorned by instruments, floating above the soft rustle and burble of visitors murmuring and shuffling underneath the cathedral’s vaulted ceilings. Solomon’s heart caught watching Hehra’s enraptured face as the choral worship imbued the air with song. Not until she turned to face him did he notice that his breathing had grown somewhat shallow, and that the dearth of oxygen to his brain was making him slightly dizzy. He took a seat and she joined him, and together they sat born aloft in canticles and psalms. Hehra’s ebullient account of the music, retreading the steps she and Solomon had taken from one monument of history to another, gladdened Rebecca’s heart.

“Sol, why don’t you take Hehra to Canterbury tomorrow? It’s a bank holiday and you can make a long weekend of it.” If she liked Westminster Abbey, Rebecca explained to Hehra, she would love Canterbury Cathedral. There was a memorial to Thomas à Becket there, and even a tomb for the famous Black Prince who died before he could be king.

Hehra’s whole person lit up, and Solomon agreed to drive her down to Kent for the weekend. The two of them set off the next day in his two-seater with small bags and hiking boots and stories and songs to share. They drove all the way to Dover and took rooms at a guest house near the chalk cliffs. They spent the following morning by the sea and then, after lunch, set out for Canterbury.

Solomon followed Hehra down the length of the cathedral, through the nave and the choir, past the sanctuary of the church elders, and finally into the Chapel of the Trinity where saints, and a king, and the slain archbishop were all enshrined in caged monuments. Immortalized in recumbent bronze effigy across the chapel from Henry IV, the Black Prince had lain for six centuries in eternal prayer to the stone vaulted heavens above, contemplating his life and his death with candor more bare than all the paeans and tributes posterity could dream up.

Tu qi paſſez oue bouche cloſe Par la ou ce corps repoſe… Hehra began to read. You who pass by with closed mouth, there where this body lies; listen to what I will tell you, for I say what I know. As you are now, so was I once; You will one day be as I am. Of death I never thought when I had life. On earth I had great riches, from which I drew great nobility: land, houses, and great treasure, clothes, horses, silver and gold.

The long epitaph on the memorial tomb was already difficult to make out, and the surrounding wrought iron railing that kept visitors at a distance only made it less intelligible. Hehra continued to read the inscription aloud under her breath, mouthing the old French words of the bygone prince’s meditation while slowly making her way around the barred-in platform and polished effigy.

But I am now poor and wretched, the unhappy Prince continued. Deep in the earth I lie. My great beauty is gone, My flesh is totally ravaged.

It was difficult for Hehra not to let such dour reflections assail her closely held memories of Mamma Akoth’s final days at the twilight of her life in the world of Time. Hehra could almost hear that beloved voice of water, telling her, with its last fragile breath, to go forth into the world, unafraid, and dare to discover the stories of peoples in far-away lands.

So narrow is my house, with me there are nothing but worms. And if you could see me now, I do not believe you would say that once I was a man, so much have I completely changed. For God’s sake, pray to the celestial King that he have mercy on my soul. For all who pray for me, or seek accord with God for me, may God give them paradise where none can be miserable. Amen.

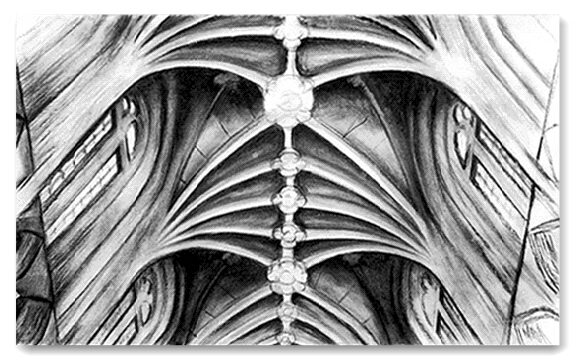

Standing apart and listening to Hehra while she read under her breath, Solomon just watched, intent and absorbed. This was perhaps the moment he would point to if ever asked when he could no longer see himself as something separate from her, or her as something separate from him. There was no flash of light, nor thunderclap, just a sense that all was well with the world. When Hehra had finished reading and contemplating the prince’s posthumous prayer, Solomon followed her back across the sanctuary and the choir, and together they caught a fleeting glimpse of the fanning vaults of the central tower, high and remote, as if meant to be secret. They continued down the nave, drawn to the oddly ornate baptismal font set on the back of the Gospel evangelists. There Hehra and Solomon sat down in silence and waited for the evensong service to begin.

Canterbury Cathedral was far less elaborate with the kind of filigreed vaults and prismatically radiant stained glass that graced the almost diaphanous Westminster Abbey. The stout clustered columns of Canterbury rising upward spread their branches out into spare vaults that bespoke a humility unknown to Westminster’s prettily bundled pillars, tiered and slender above, their fingers stretched to touch tips at the apex of the vaulted ceiling of the nave. Drawing the visitor’s eye heavenward to the greater glory of God, the columns evoked visions of a standing forest of stone, and the murmur and shuffle of conversations and feet mingled to make the same forest sounds as in Nature in both houses of worship, as if the unguarded noise of living things in creation were simply the true language of Heaven.

Here, too, at Canterbury, art song rose through the rustling gurgle of tourists milling around the cathedral. The stone vaults of the church ceiling smoothed out the keen edges of children’s voices intoning the opening prayer, first in unison and then, with dilating time, in a gradual cascade of overlapping harmonies, each vowel drawn, unhurried, speaking, surely, the language of saints. At that moment, Hehra’s thoughts grew even more saturated with her memories of Mamma Akoth, the silence that now filled the space that she had left bereft with her passing out of the world of Time feeling even more profound. Mamma Akoth would love this, she thought, and Esther, too, and Maya. Hehra found herself imagining how the resonant sounds of the choral Evensong might look to her afflicted sister’s uncommon eye. She herself heard only music and felt the sea of her soul swell and overflow into tears that sprang forth unbidden in a wave that was joy and saudade combined. With each turn of harmony, the tide surged within and soon, Hehra just let herself weep without making a sound, unmindful of dissembling. Beside her, Solomon felt the heat rising from her brimming heart and just as he had collected her words with shining eyes, he collected her silence as well, placing the palm of his right hand on the back of her neck with weightless tenderness.

This was the moment that Hehra would point to if ever asked when she could no longer see herself as something separate from Solomon, or him as something separate from her. And so they sat, alone for a while after the final tones of the Evensong had vanished into the vaulted ceiling, Solomon’s arm moving to circle Hehra’s shoulder and hold her close, Hehra letting his serenity settle all her unspoken disquiet.

“Esther and Maya would love this,” was all she said, once they resolved to depart.

Solomon tucked a stray lock of twisted hair that fell over her eyes back among the other braids. Then Hehra led the way out of the cathedral beneath the clustered columns rising to uphold a heaven of vaulted stone, and Solomon followed close by her side.